What We Learned During Isabel Wilson's Internship

Isabel Wilson, from University of Washington’s Program on the environment, joined us Winter Quarter 2021 to do an internship as part of her senior Capstone project. Due to COVID, the internship was entirely remote, with Isabel and Melissa meeting via Zoom and transmitting data visualizations back and forth.

Isabel wanted to explore Stillwaters’ bird survey data, which has been collected monthly since 2003 by volunteers. It is a complex dataset as the number of sites in the lower Carpenter Creek watershed visited by Stillwaters birders varies seasonally and has changed somewhat over the years. Isabel decided to focus on the two sites that have been surveyed the longest and year around: Appletree Cove from Arness Park and the Kingfisher lobe of the Kingston Estuary (AKA the Slough) on the other side of the South Kingston Road.

As the birders always survey on the first Monday of each month, starting between 7:30 and 8:30 in the morning, the tide levels during surveys varied predictably with season. Thus, observations were mostly at higher tides in the winter and lower tides in the spring. Not surprisingly, tide level affected the number and species of birds seen, as tidal water drains out of the estuary at below a 5 ft tide and the Cove is mostly drained below a 4 ft tide. But separating the effects of tide level from the effects of season on the birds is challenging, and until you do it is difficult to say whether seeing more or fewer of a species in July versus December is due to their preferring low tides or summer versus high tides or winter. Isabel only had 10 weeks.

After much consideration, we decided not to address tidal or seasonal variation, but rather to compare two time periods: the approximately 4 years before culvert removal began on South Kingston Rd. in 2011 and the approximately 4 years after the bridge was finished in 2012. I say “approximately” because the idea was to keep the span of time and number of survey days before and after bridge construction as similar as possible, so that representation of seasons and tides levels in the surveys would be the same. Happily, this now allows us to talk about ‘friendlier’ numbers with school kids as well as adults: the total number of birds observed before and after instead of an average number per year. So, for example, it is equally meaningful to talk about 23 eagles over 4 years, as 5.75 eagles per year because the same number of years are involved.

Isabel also considered which groups or species of birds would be most likely to change their behavior in response to the new fish passage. She settled on fish-eating birds because the primary goal of the culvert removal was to increase fish access to the estuary. The fish species that benefit are not only salmonids, but forage fish, like sand lance, that are an important part of the marine food chain, and year around cove denizens like surf perch and sculpins (which we’ve caught foraging high in the salt marsh north of West Kingston Road during high tides).

However, ‘fish-eating birds’ is still a very diverse group which includes winter migrants like goldeneye and mergansers, summer residents like Osprey, and longer-term residents like Bald Eagles and Great Blue Herons. Ultimately, Isabel’s analyses focused on three species observed in all seasons: Bald Eagles, Great Blue Herons, and Belted Kingfishers. Her question was whether the culvert removal changed the frequency with which these birds were observed in the estuary versus cove. If fish were able to better access the estuary after the culvert removal, then she hypothesized that these birds would follow suit and be seen in the estuary more as well.

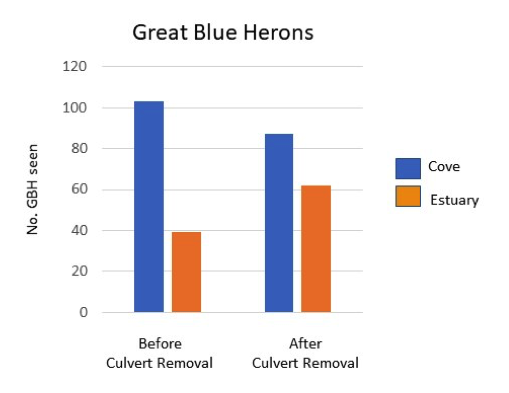

Below are three graphs showing the results of her analyses. Figure 1 shows the change in distribution of the most commonly seen fish-eating species in the lower watershed, the Great Blue Heron.

Isabel wanted to explore Stillwaters’ bird survey data, which has been collected monthly since 2003 by volunteers. It is a complex dataset as the number of sites in the lower Carpenter Creek watershed visited by Stillwaters birders varies seasonally and has changed somewhat over the years. Isabel decided to focus on the two sites that have been surveyed the longest and year around: Appletree Cove from Arness Park and the Kingfisher lobe of the Kingston Estuary (AKA the Slough) on the other side of the South Kingston Road.

As the birders always survey on the first Monday of each month, starting between 7:30 and 8:30 in the morning, the tide levels during surveys varied predictably with season. Thus, observations were mostly at higher tides in the winter and lower tides in the spring. Not surprisingly, tide level affected the number and species of birds seen, as tidal water drains out of the estuary at below a 5 ft tide and the Cove is mostly drained below a 4 ft tide. But separating the effects of tide level from the effects of season on the birds is challenging, and until you do it is difficult to say whether seeing more or fewer of a species in July versus December is due to their preferring low tides or summer versus high tides or winter. Isabel only had 10 weeks.

After much consideration, we decided not to address tidal or seasonal variation, but rather to compare two time periods: the approximately 4 years before culvert removal began on South Kingston Rd. in 2011 and the approximately 4 years after the bridge was finished in 2012. I say “approximately” because the idea was to keep the span of time and number of survey days before and after bridge construction as similar as possible, so that representation of seasons and tides levels in the surveys would be the same. Happily, this now allows us to talk about ‘friendlier’ numbers with school kids as well as adults: the total number of birds observed before and after instead of an average number per year. So, for example, it is equally meaningful to talk about 23 eagles over 4 years, as 5.75 eagles per year because the same number of years are involved.

Isabel also considered which groups or species of birds would be most likely to change their behavior in response to the new fish passage. She settled on fish-eating birds because the primary goal of the culvert removal was to increase fish access to the estuary. The fish species that benefit are not only salmonids, but forage fish, like sand lance, that are an important part of the marine food chain, and year around cove denizens like surf perch and sculpins (which we’ve caught foraging high in the salt marsh north of West Kingston Road during high tides).

However, ‘fish-eating birds’ is still a very diverse group which includes winter migrants like goldeneye and mergansers, summer residents like Osprey, and longer-term residents like Bald Eagles and Great Blue Herons. Ultimately, Isabel’s analyses focused on three species observed in all seasons: Bald Eagles, Great Blue Herons, and Belted Kingfishers. Her question was whether the culvert removal changed the frequency with which these birds were observed in the estuary versus cove. If fish were able to better access the estuary after the culvert removal, then she hypothesized that these birds would follow suit and be seen in the estuary more as well.

Below are three graphs showing the results of her analyses. Figure 1 shows the change in distribution of the most commonly seen fish-eating species in the lower watershed, the Great Blue Heron.

Similar numbers of herons were observed before and after culvert removal (142 versus 149 respectively), but after culvert removal, herons were more often seen in the estuary. As many of these were undoubtedly the same birds observed repeatedly, we can say that local herons were spending more of their time in the estuary after the culvert had been removed than they had before (and less time in the cove).

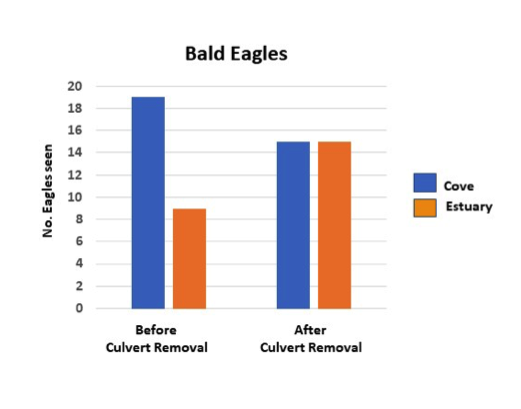

Our data on bald eagles followed a similar pattern.

Our data on bald eagles followed a similar pattern.

Eagles were twice as likely to be observed in the cove versus the estuary before culvert removal but were equally likely to be seen in both after the bridge was built. For both of these species, removal of the culvert did not increase or decrease the numbers of birds seen (or the frequency with which the birds were seen as they were most likely the same birds observed each month) but it did affect where specifically they spent their time.

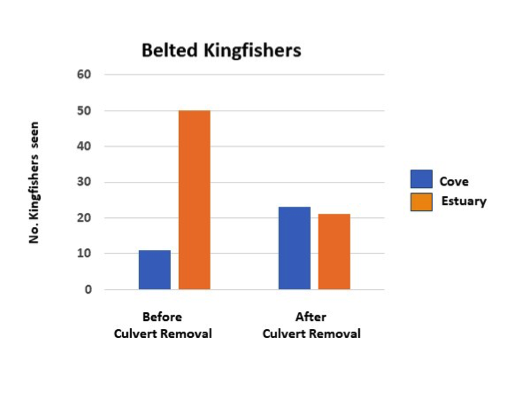

The Belted Kingfishers appear to have responded to the new bridge somewhat differently.

The Belted Kingfishers appear to have responded to the new bridge somewhat differently.

There were fewer kingfisher sightings after the culvert removal (44 down from 61) and they were much less often observed in the estuary. Why have the kingfishers responded differently than the herons and eagles? Why might the estuary be less attractive to them post-culvert removal?

This is where the years of collective experience of the Stillwaters’ birders proved helpful beyond the data they collected. Obviously, many variables affect the presence or absence of birds in a location at a given time and while the heron and eagle data are consistent with our hypothesis, hypotheses are not proven in science, just supported or refuted. Anecdotal observations are helpful in generating more and better hypotheses to test, so researchers are happy to hear people speculate about why data turn out the way they do.

Putting our heads together with the volunteers who collected the data, Isabel and I came up with a couple likely explanations of the kingfishers’ behavior. First, the causeway over the culvert under South Kingston Road used to have phone lines strung all the way across it, but the new bridge does not. The kingfishers were regularly seen perching on the phone lines watching for fish in the water below and now they have to find other places to fish from. Second, when water rushed in and out through the 10 ft box culvert, ‘scour holes’ were created on either side that were four to six feet deep. Small fish were regularly trapped in these holes at low tides, making them particularly easy prey for aerial diving birds like kingfishers. These scour holes were filled in during bridge construction as part of the Army Corps of Engineers’ plan to make the fish passage more friendly for salmon. Either or both of these changes during culvert removal may have been factors in the kingfishers’ frequenting the estuary less often afterwards. Although the ‘phone line’ and ‘scour hole’ hypotheses can’t be tested retroactively around the South Kingston Bridge, these results and speculations still provide food for thought to researchers designing future studies about how human activities may impact specific bird species in small, unplanned ways.

This is where the years of collective experience of the Stillwaters’ birders proved helpful beyond the data they collected. Obviously, many variables affect the presence or absence of birds in a location at a given time and while the heron and eagle data are consistent with our hypothesis, hypotheses are not proven in science, just supported or refuted. Anecdotal observations are helpful in generating more and better hypotheses to test, so researchers are happy to hear people speculate about why data turn out the way they do.

Putting our heads together with the volunteers who collected the data, Isabel and I came up with a couple likely explanations of the kingfishers’ behavior. First, the causeway over the culvert under South Kingston Road used to have phone lines strung all the way across it, but the new bridge does not. The kingfishers were regularly seen perching on the phone lines watching for fish in the water below and now they have to find other places to fish from. Second, when water rushed in and out through the 10 ft box culvert, ‘scour holes’ were created on either side that were four to six feet deep. Small fish were regularly trapped in these holes at low tides, making them particularly easy prey for aerial diving birds like kingfishers. These scour holes were filled in during bridge construction as part of the Army Corps of Engineers’ plan to make the fish passage more friendly for salmon. Either or both of these changes during culvert removal may have been factors in the kingfishers’ frequenting the estuary less often afterwards. Although the ‘phone line’ and ‘scour hole’ hypotheses can’t be tested retroactively around the South Kingston Bridge, these results and speculations still provide food for thought to researchers designing future studies about how human activities may impact specific bird species in small, unplanned ways.